Emotional States Excerpts

from García’s Art of Singing II (1847)

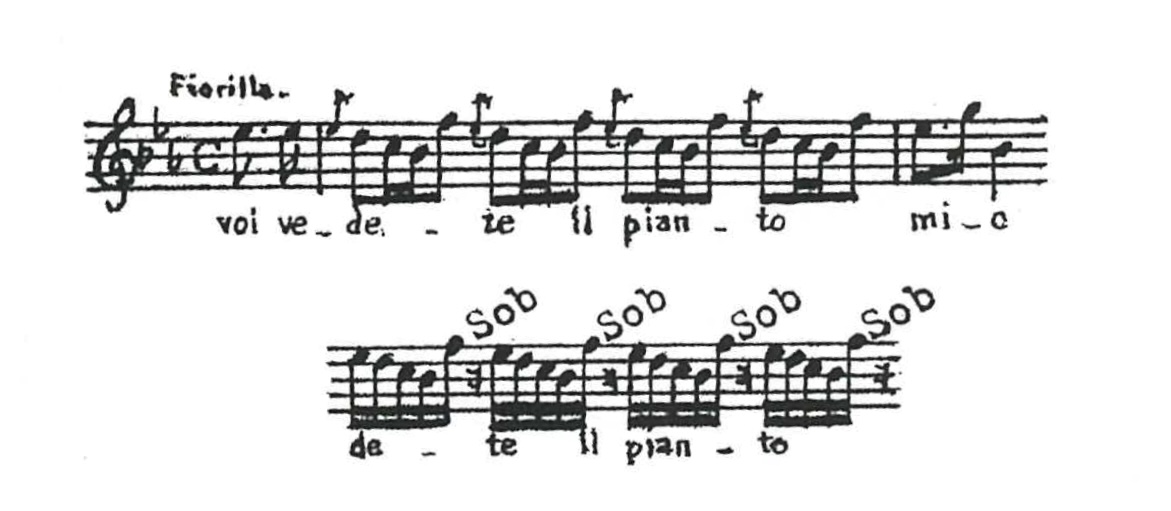

Sighs and Sobs

“Les soupirs, dans toutes leurs variétés, sont produits par le frottement plus ou moins fort, plus ou moins prolongé, de l’air contre les parois du gosier, soit que l’on introduise l’air dans la poitrine, soit qu’on l’en chasse. Lorsqu’on use du premier moyen, on peut modifier le frottement de manière à obtenir le sanglot, le râle même, si les cordes vocales sont mises en jeu. Les sanglots s’obtiennent par une aspiration courte et saccadée.”

Translation: “Sighs, in all their varieties, are produced by the more or less strong, more or less prolonged friction of the air against the walls of the throat, whether one draws air into the chest or expels it. When using the first method, one can modify the friction in such a way as to obtain sobbing, even a rattle, if the vocal cords are brought into play. Sobs are obtained through short and jerky inhalation.”

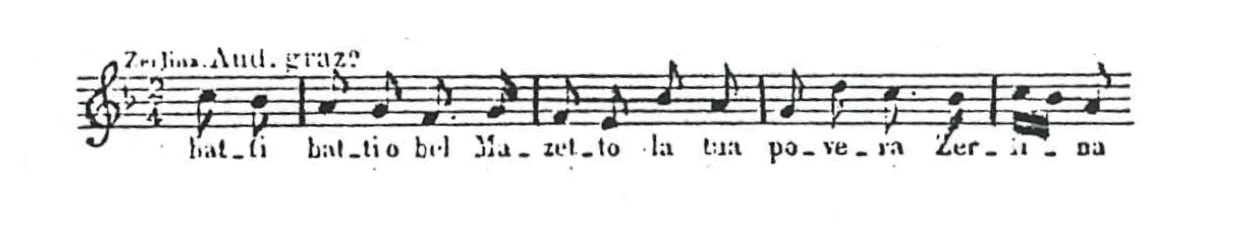

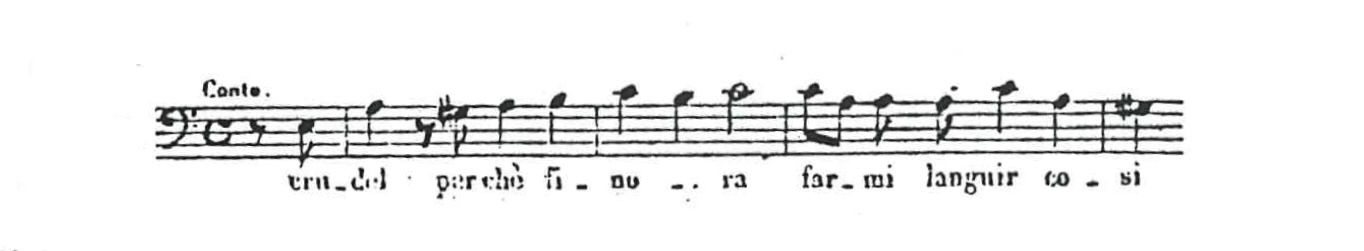

“Voi Vedete il pianto mio,” Scene II (no.7), from Turco in Italia, Rossini, pp.145

Scene: Geronio has just scolded his wife, Fiorilla, for flirting with the Turkish nobleman. Fiorillia is denying her husband’s claims, declaring he has offended her.

Translation: “you see my crying”

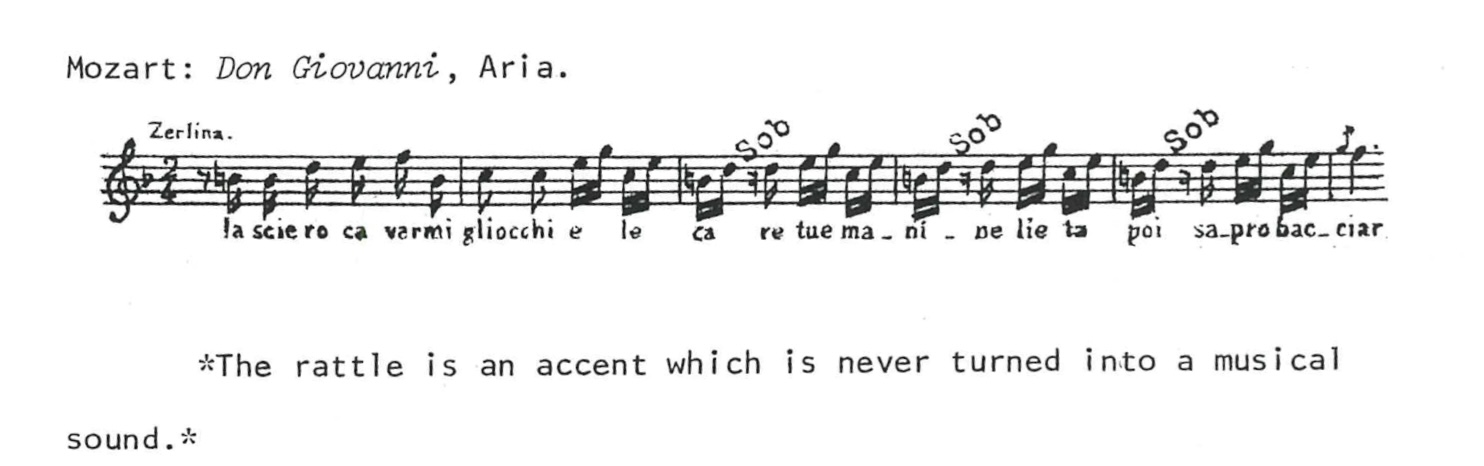

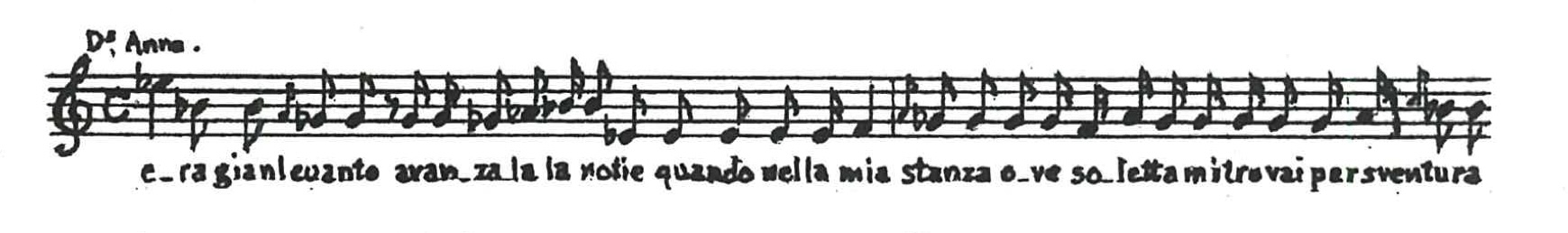

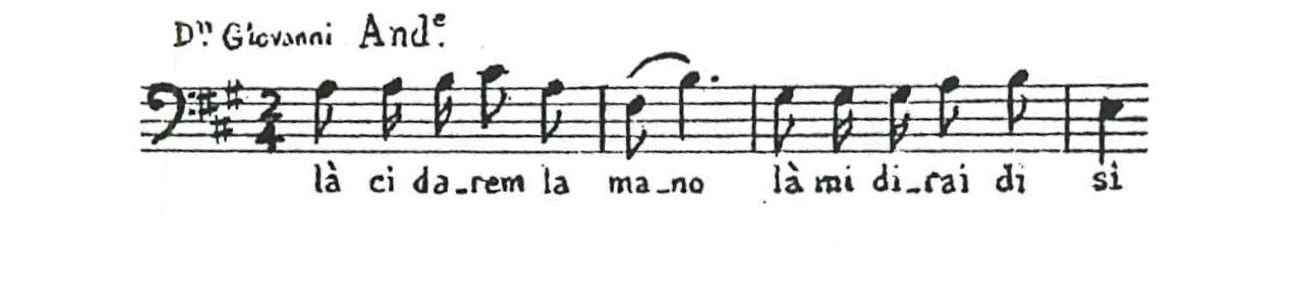

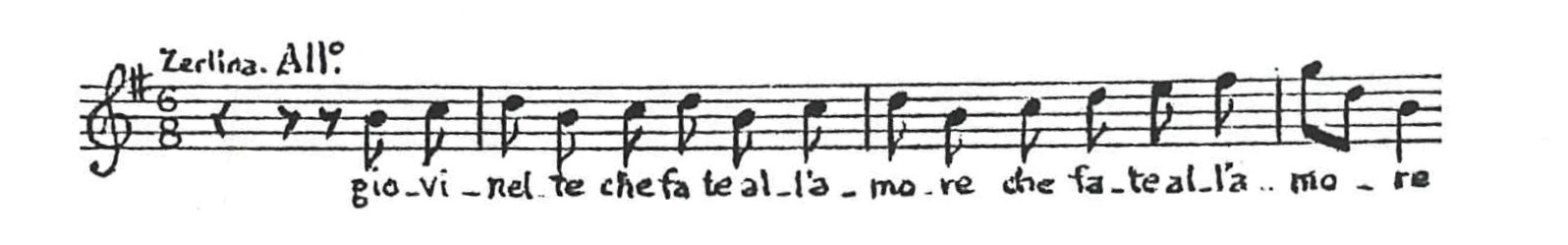

“La sciero ca varmi gliocchi…,” Batti Batti, from Don Giovanni, Mozart, pp.145

Scene: After almost falling for Don Giovanni’s flirtations, the young peasant girl, Zerlina, comforts her fiancé, Masetto, reassuring him of her love and commitment.

Translation: “I would let my eyes be gouged out, and then I will know how to kiss your dear little hands gladly.”

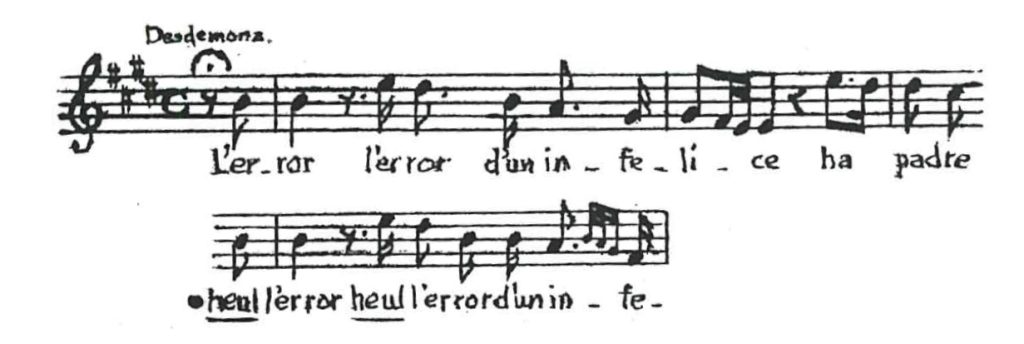

“Le râle est un accent qui ne se transforme jamais en son musical. Lorsqu’on a recours au deuxieme moyen, c’est-à-dire à l’expulsion de l’air, on produit le soupir proprement dit et le gémissement. Le soupir précède une note ou la suit. Quand le soupir précède la note, si elle est placée sur une voyelle, il la convertit en une expiration chantée; si elle est placée sur une consonne, il forme, devant cete consonne, le son heu! aspiré.”

Translation: “The rattle is an accent that never transforms into a musical sound. When one uses the second method—that is to say, the expulsion of air—one produces the sigh properly speaking, and the moan.The sigh either precedes a note or follows it. When the sigh precedes the note, if the note is placed on a vowel, it converts it into a sung exhalation; if it is placed on a consonant, it forms, before that consonant, the aspirated sound heu!”

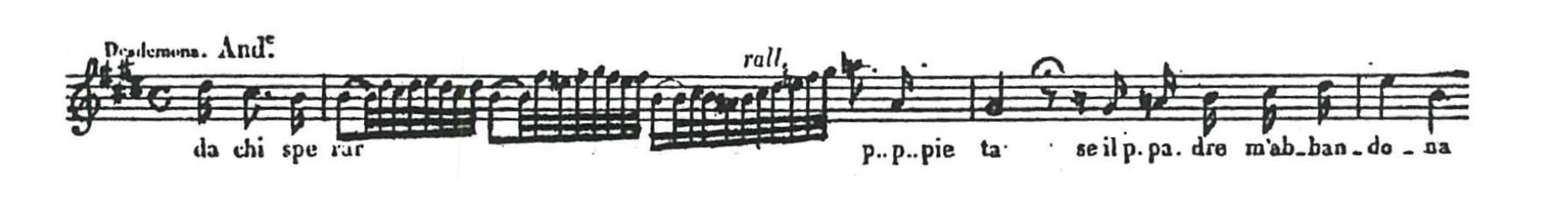

“L’error l’error,” Act II Scene XI, from Otello, Rossini, pp.146

Scene: Otello has accused Desdemona of being unfaithful to him. In this scene she is begging her father to pardon her sins.

Translation: “The mistake, the mistake of a wretched (unhappy) man, ah father.”

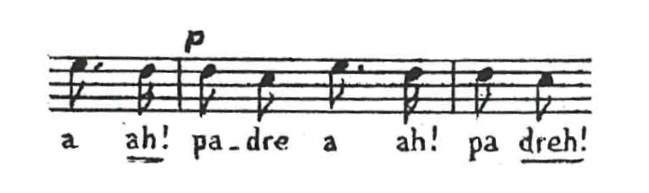

“Quand le soupir achève la note, c’est par une forte expulsion de l’air qu’il se produit.”

Translation: “When the sigh completes the note, it occurs through a strong expulsion of air.”

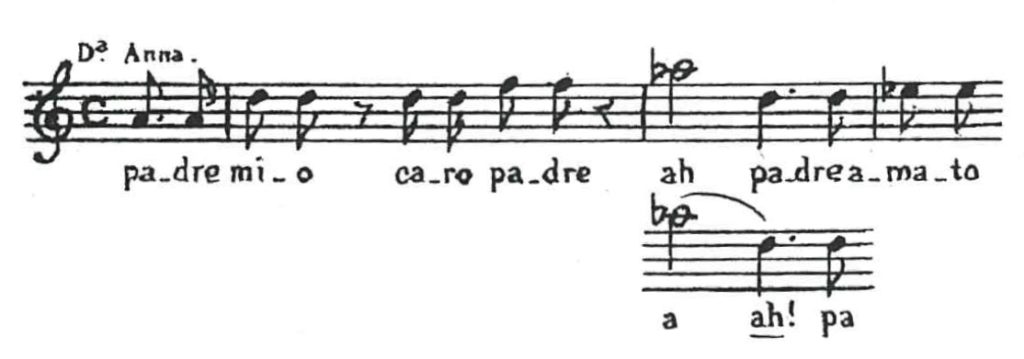

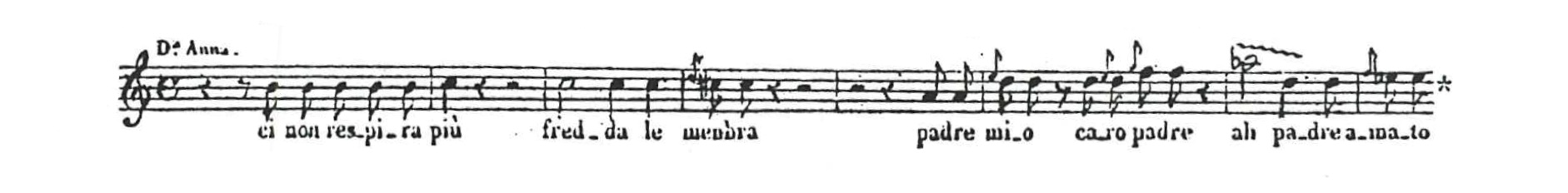

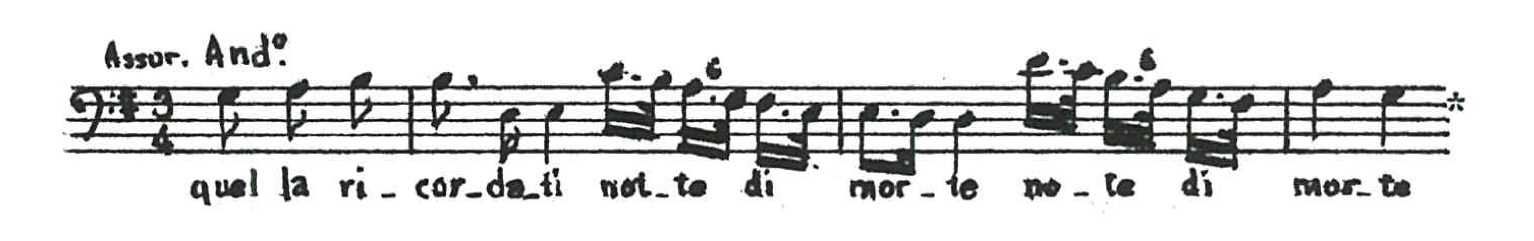

“Padre Mio,” Act I Scene II Recitative and Duet, from Don Giovanni, Mozart, pp.146

Scene: Donna Anna has just returned home with her husband Don Ottavio to find her father, the Commendatore, murdered.

Translation: “my father, dear father, beloved father.”

“Ou bien on laisse d’abord tomber la voix pour chasser ensuite l’air, ce qui produit la plainte.”

Translation: “Or one first lets the voice drop, then expels the air afterward, which produces the lament.”

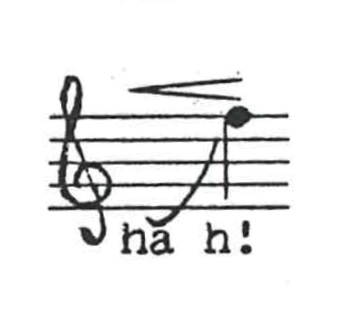

“Le soupir s’obtient encore au moyen d’unport de voix ascendant que l’on assourdit par le bruit de l’air. Ce port de voix, à sa naissance, ne doit être que le frottement de l’air.”

Translation: “The sigh is also produced by means of an ascending port de voix (portamento) that is muffled by the sound of the air. At its onset, this port de voix should be nothing more than the friction of the air.”

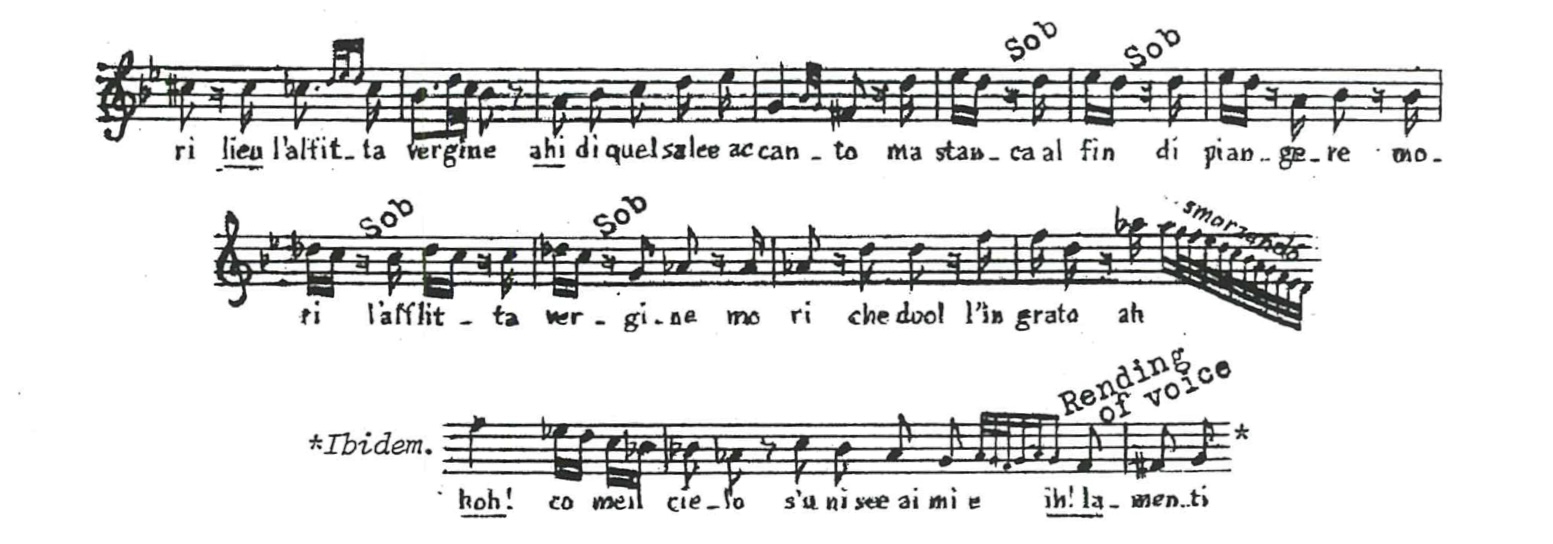

“Ajoutons enfin que l’expiration produit encore une espèce de frottement ou de déchirement de la voix; mais, bien que l’effet en soit dramatique, l’étude en est trop pénible pour que nous osions la conseiller.

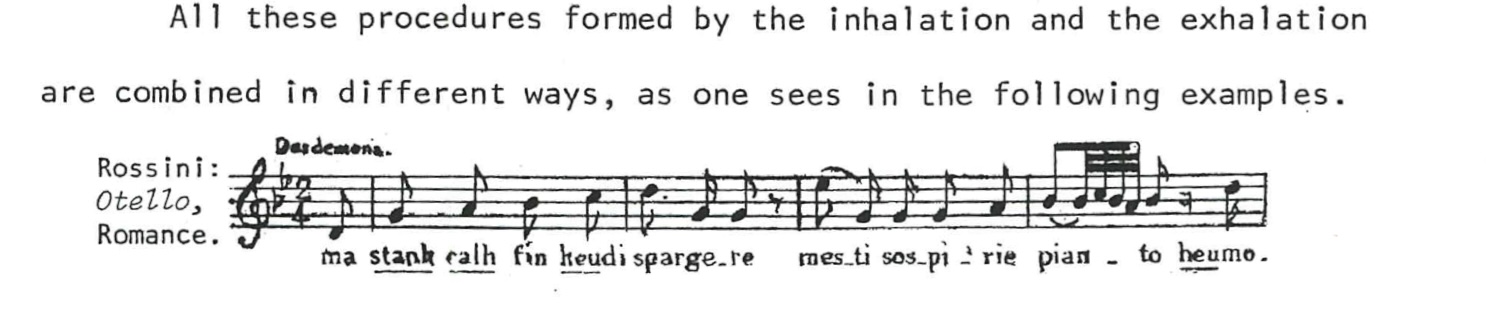

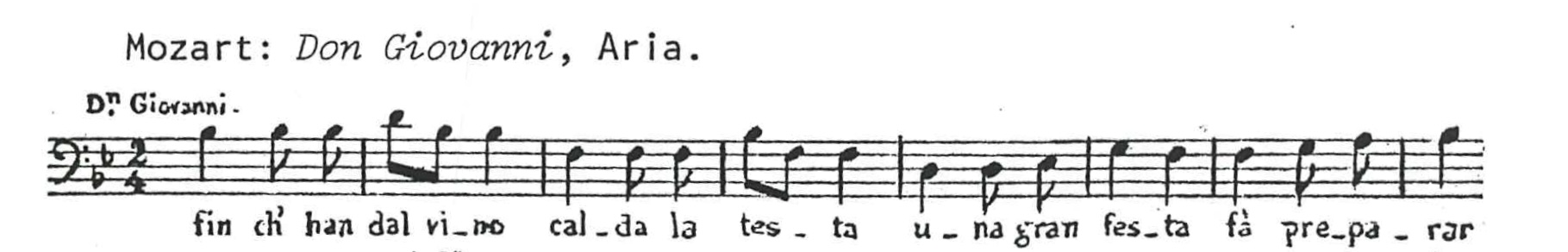

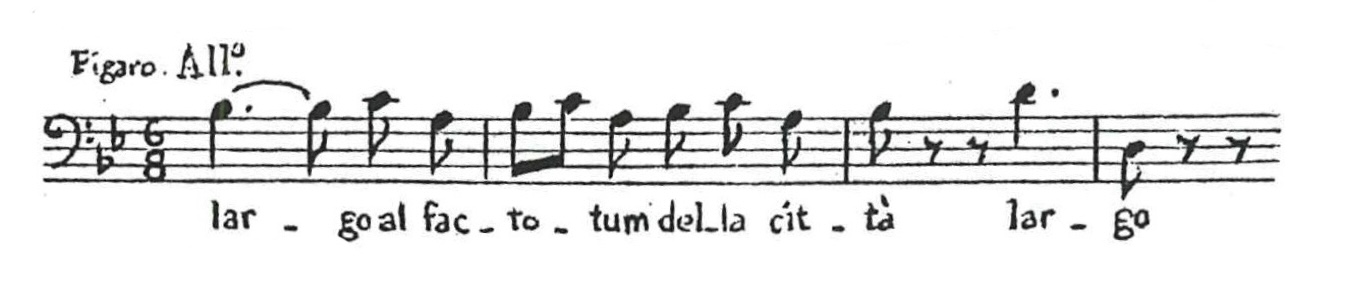

Tous ces procédés formés par l’inspiration et l’expiration se combinent de différentes manières, comme on le voit dans les exemples suivants.”

Translation: “Let us add, finally, that exhalation also produces a kind of friction or tearing of the voice; but although the effect is dramatic, the practice is too taxing for us to dare recommend it. All these techniques formed by inhalation and exhalation combine in different ways, as can be seen in the following examples.”

“Ma Stan,” Act III Scene II Scena e Romanza, from Otello, Rossini, pp.146-147

Scene:

Translation: “But finally tired of shedding mournful sighs and tears, the afflicted maiden died—ah!—beside that willow! But finally tired of crying, the afflicted maiden died, died… What grief! The ungrateful one… the ungrateful one… Alas! Tears will not let me go on.”

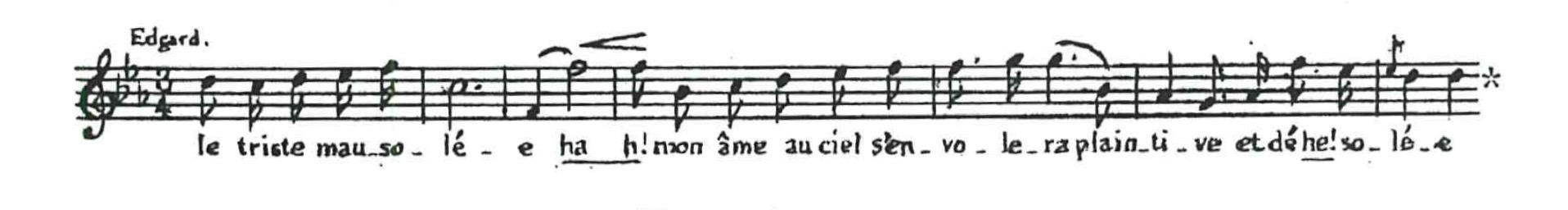

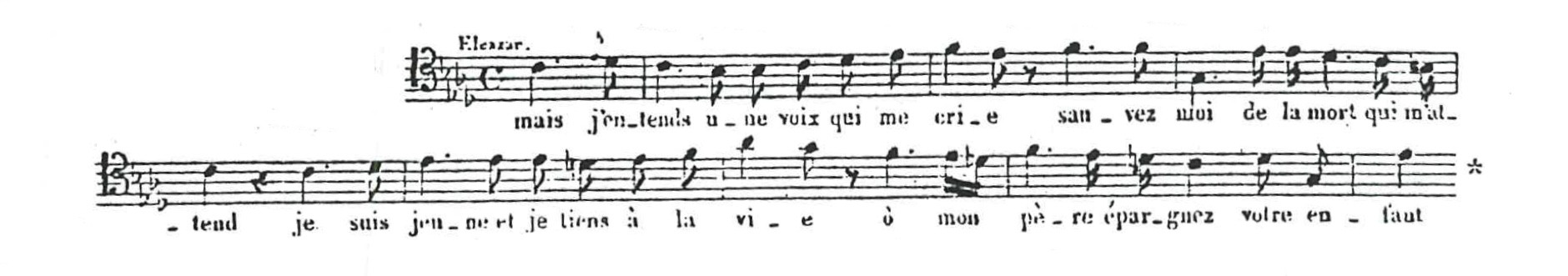

“Le Triste” Act III Scene 15, Lucia di Lammermoor (French edition), Donizetti, pp.147

Scene:

Translation: “the sad mausoleum… ah, my soul to heaven will fly away, plaintive and desolate.”

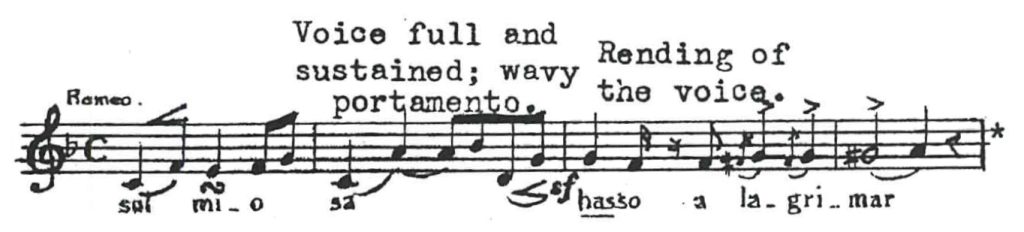

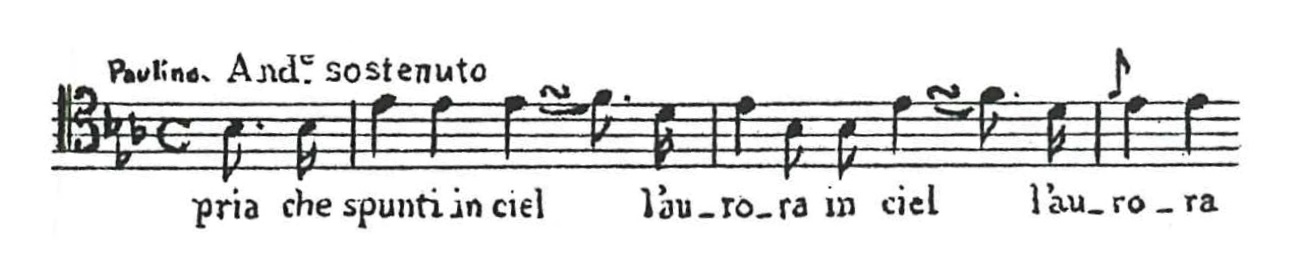

“Sul Mio,” Scena Aria e Duetto “Oh se tu dormi, svegliati,”from Romeo e Giulietta, Vaccai, pp.147

Scene:

Translation: “on my rock to weep.”

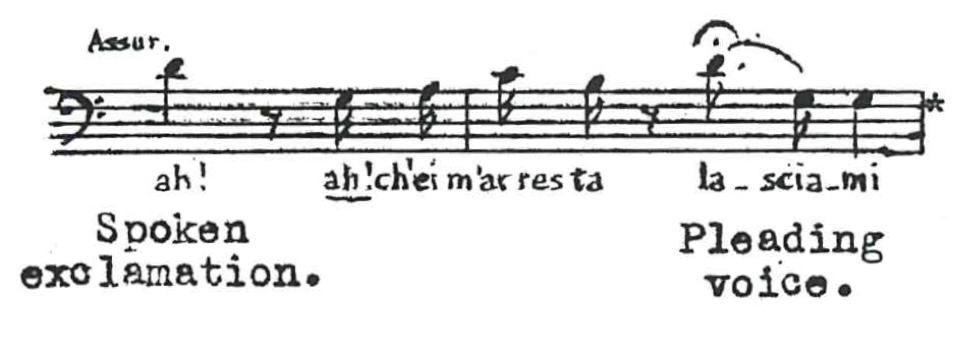

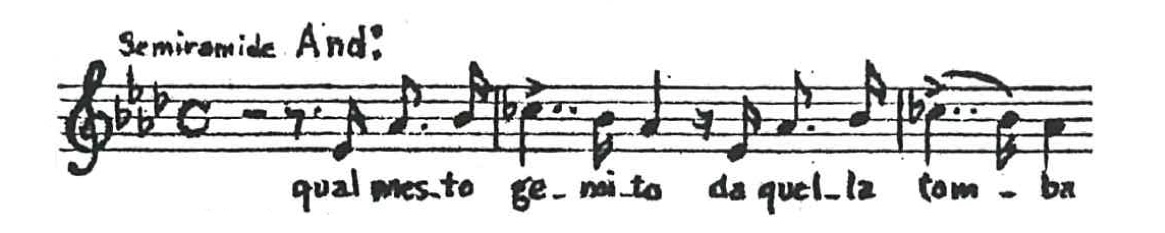

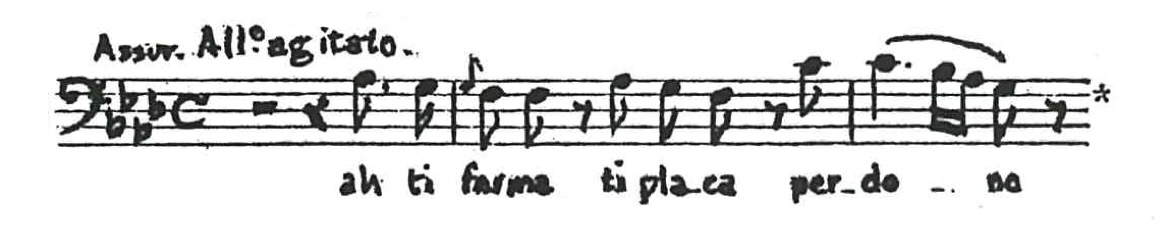

“Ah ch’ei m’arresta…,” Act 2, Scene 8 from Semiramide, Rossini, pp.147

Scene: Assur

Translation: “ah! that he stops me—leave me.”

Agitation

Il est une espèce d’agitation intérieure qui nous vient de la plénitude d’un sentiment éprouvé, et qui se trahit au dehors par l’altération ou le nerf de la voix et du débit. Cet état de l’âme, qui s’appelle l’émotion, est la disposition nécessaire où doit se placer quiconque veut agir puissamment sur les autres. Si cette agitation a pour cause l’indignation, la joie excessive, la terreur, l’exaltation, etc., la voix sort par une espèce de secousse.

Translation: “There is a kind of inner agitation that comes to us from the fullness of a feeling we have experienced, and which reveals itself outwardly through the alteration or tension of the voice and delivery. This state of the soul, called emotion, is the necessary disposition in which anyone who wishes to act powerfully upon others must place themselves. If this agitation is caused by indignation, excessive joy, terror, exaltation, etc., the voice comes out with a kind of jolt.”

Agitation Caused by Fear

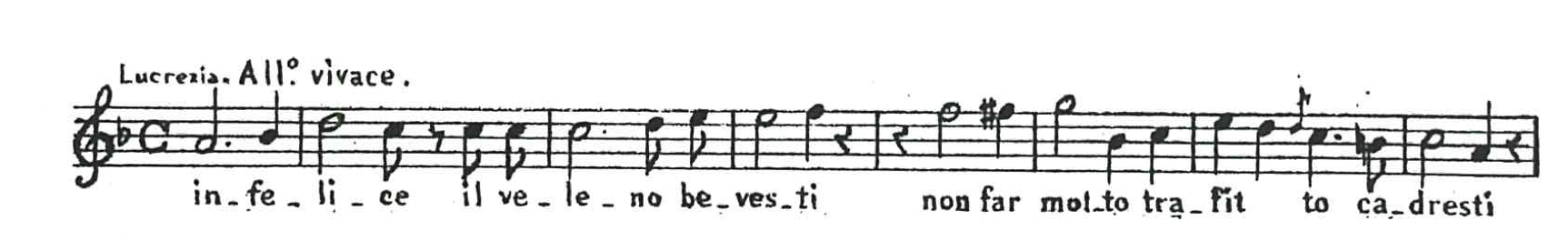

“Infelice il veleno bevesti…” Act 1, Scene 13 from Lucrezia Borgia, Donizetti, pp.149

Scene: Gennaro has been poisoned by Lucrezia’s husband, Don Alfonzo. The sorceress, Lucrezia rushes to Gennaro to give him the antidote.

Translation: “Unhappy one! You drank the poison, do not utter a word, you would fall pierced.”

Agitation Caused by Joy

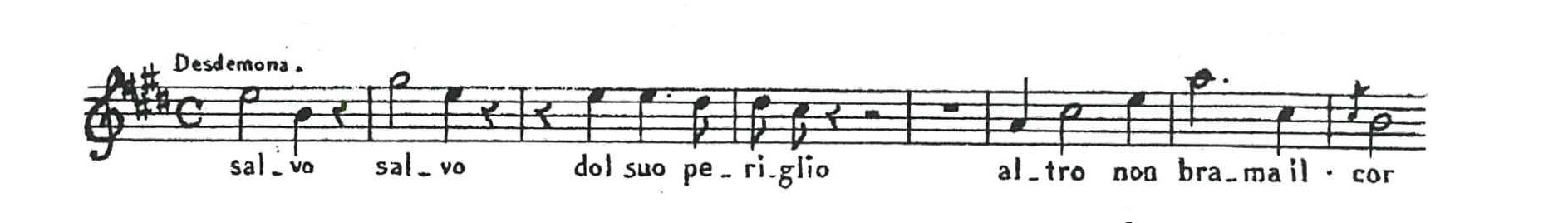

“Salvo Salvo dol suo periglio…” Act 2 Scene 10 from Otello, Rossini, pp.149

Scene:

Translation: “Safe, safe from his peril? The heart desires nothing else”

Agitation Caused by Indignation

“Quegli è il carnefice…” Act 1 Scene 21 from Don Giovanni, Mozart. pp149

Scene: Donna Anna talking to Don Ottavio

Translation: “That man is the executioner of my father. (…) Doubt no longer: the last words that the wicked one uttered.”

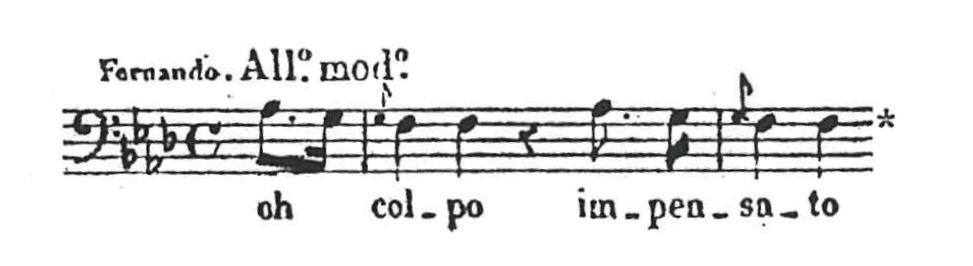

Agitation Caused by Indignation and Anger

“Vituperio disonore…” Act 1, Scene 9, La Gazza Ladra, Rossini, pp.149

Scene: sung by Fernando

Translation: “Insult! Dishonour! I have tolerated enough. A mature man and a magistrate, you ought to be ashamed.”

Agitation Caused by Fear and Remorse

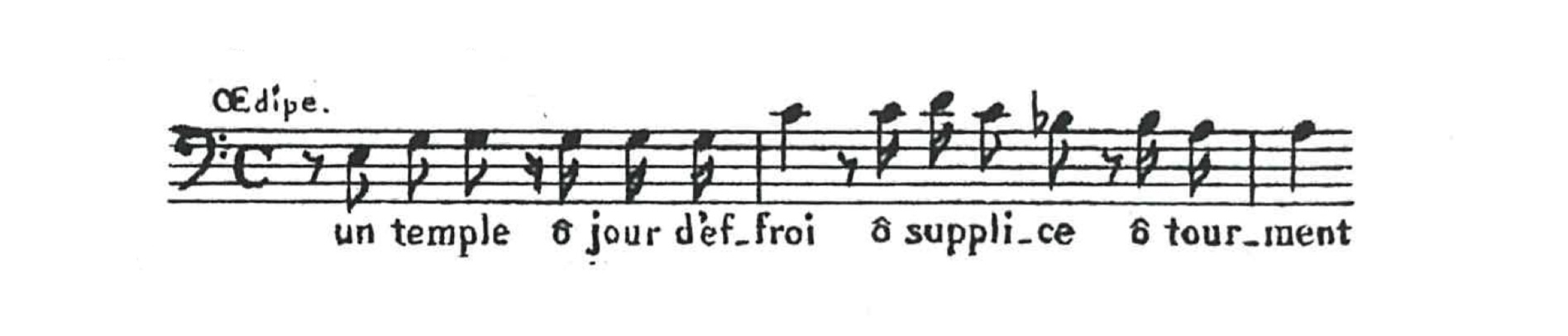

“Un temple ô jour…” Act 2, No. 11 from Œdipe à Colone, Sacchini, pp.149

Scene: Sung by Œdipe

Translation: “A temple, O day of dread, O torment, O anguish.”

Agitation Caused by Indignation, Contempt and Despair

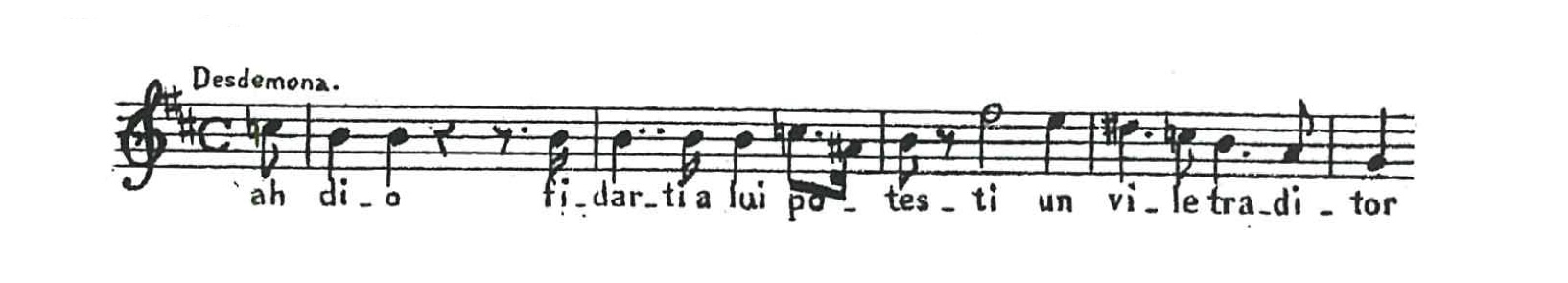

“Ah dio fidarti,” Act 3 Scene 3 (Finale), Otello, Rossini pp.149

Scene:

Translation: Oh God! Could you trust yourself to him? To a vile traitor?

Grief

Lorsque la mème agitation est produite par une douleur si vive qu’elle nous domine complétement, l’organe éprouve une sorte de vacillation qui se communique à la vois. Cette vacillation s’appelle tremolo. Le tremolo, motivé par la situation et conduit avee art, est d’un effet pathétique, assuré.

Translation: When the same agitation is produced by a pain so sharp that it completely dominates us, the organ experiences a kind of wavering which is transmitted to the voice. This wavering is called tremolo. The tremolo, justified by the situation and carried out with art, has a surely pathetic (emotion-arousing) effect.

“Pensa che son tuo sangue…” Act 2 Finale Qual cor tradisti, qual cor perdesti from Norma, Bellini, pp.150

Scene:

Translation: “Think that they are your blood (family)… have pity on them, ah! Father, have for them, for them pity.”

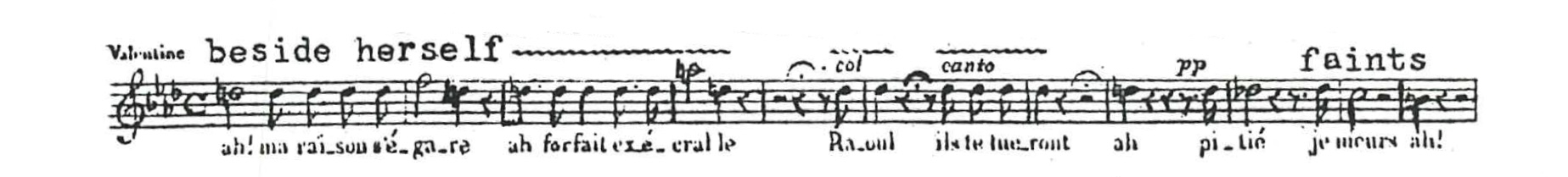

“Ses jours…” Guillaume Tell, Rossini, pp.150

Ne chantez pas, mais déclamez avec une voix déchirante et dans le plus grand désordre, les mots: Raul! ils te tueront puis la respiration op pressée et défaillante, achevez les mots ah! pitié! je meurs! ah!

“Do not sing, but declaim with a heart-rending voice and in the greatest disorder, the words: Raul! they will kill you then the breathing oppressed and failing, finish the words ah! mercy! I am dying! ah!”

Le trémolo ne doit être employé que pour peindre les sentiments qui, dans la vie réelle, nous émeuvent profondément: l’angoisse de voir quelqu’un qui nous est cher dans un danger imminent, les larmes que nous arrachent certains mouvements de colère ou de vengeance, etc. Dans ces circonstances mêmes, exagère l’expression ou la durée, il devient fatigant et disgracieux. Hors les cas spéciaux que nous venons d’indiquer, il faut se garder d’altérer en rien l’assurance du son, car l’usage réitéré du tremblement rend la voix chevrotante. L’arliste qui a contracté cet intolérable défaut devient incapable de phraser aucune espèce de chant soutenu. C’est ainsi que de belles voix ont été perdues pour l’art.

Le chevrotement de la voix n’est, dans tous les cas possibles, qu’une affectation de sentiment que certaines personnes prennent pour un sentiment véritable. Quelques chanteurs croient, à tort, rendre par ce moyen leur voix plus vibrante, et, de même que plusieurs violonistes, cherchent à augmenter la force de leur instrument par l’ondulation du son. La voix ne peut vibrer que grâce à l’éclat du timbre et à la puissance de l’émission de l’air, et non par l’effet du tremblement.

“The tremolo must be employed only to depict feelings which, in real life, move us deeply: the anguish of seeing someone dear to us in imminent danger, the tears drawn from us by certain outbursts of anger or vengeance, etc. Even in these circumstances, if the expression or the duration is exaggerated, it becomes tiring and ungainly. Outside the special cases we have just indicated, one must be careful not to alter in any way the steadiness of the tone, for repeated use of trembling makes the voice quavering. The artist who has acquired this intolerable defect becomes incapable of phrasing any kind of sustained singing. Thus many fine voices have been lost to art.

The quavering of the voice is, in all possible cases, nothing more than an affectation of feeling which certain people mistake for genuine feeling. Some singers wrongly believe that by this means they make their voice more vibrant, and, like several violinists, seek to increase the power of their instrument by undulating the sound. The voice can vibrate only through the brilliance of the timbre and the power of the emission of air, and not through the effect of trembling.”

La menace contenue, la douleur profonde et le désespoir concentré prennent un timbre eaverneux.

The contained threat, the deep pain, and the concentrated despair take on a cavernous timbre.

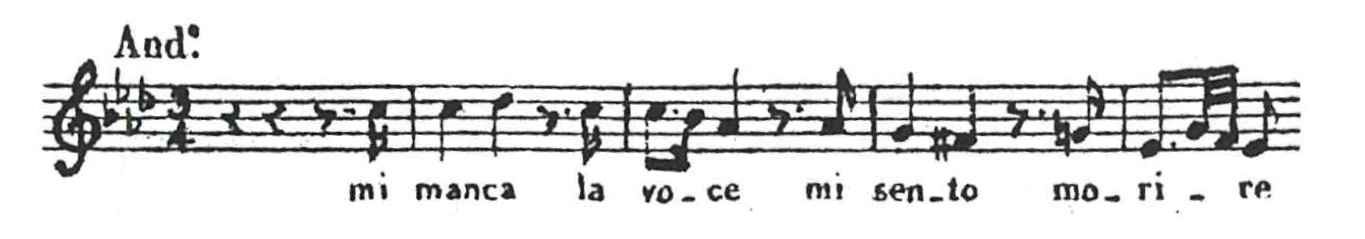

Profound Grief

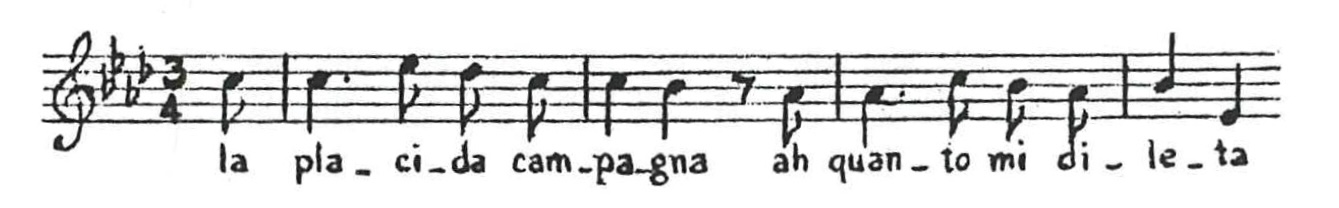

Ici les accents de douleur sont nuancés, tantôt par une teinte de mélancolie, tantôt par des éclats de douleur, tantôt par un sombre désespoir.

“Here the accents of pain are nuanced, sometimes by a shade of melancholy, sometimes by bursts of pain, sometimes by a dark despair.

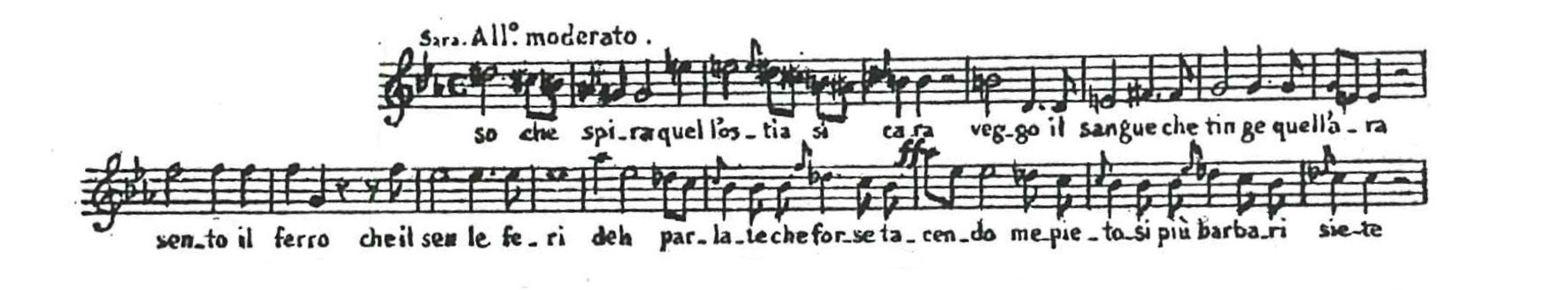

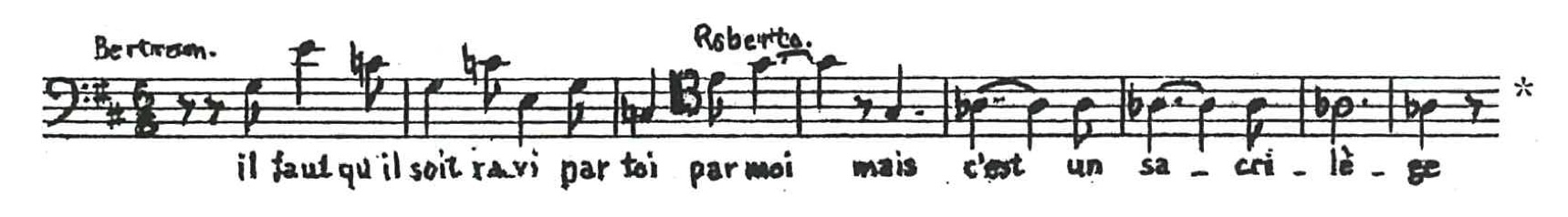

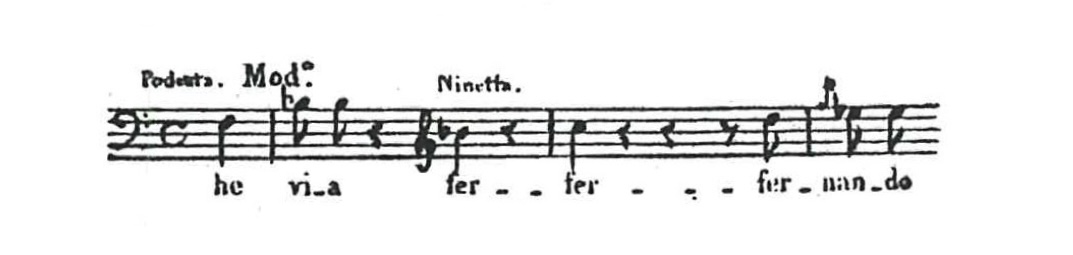

Heart-rending grief

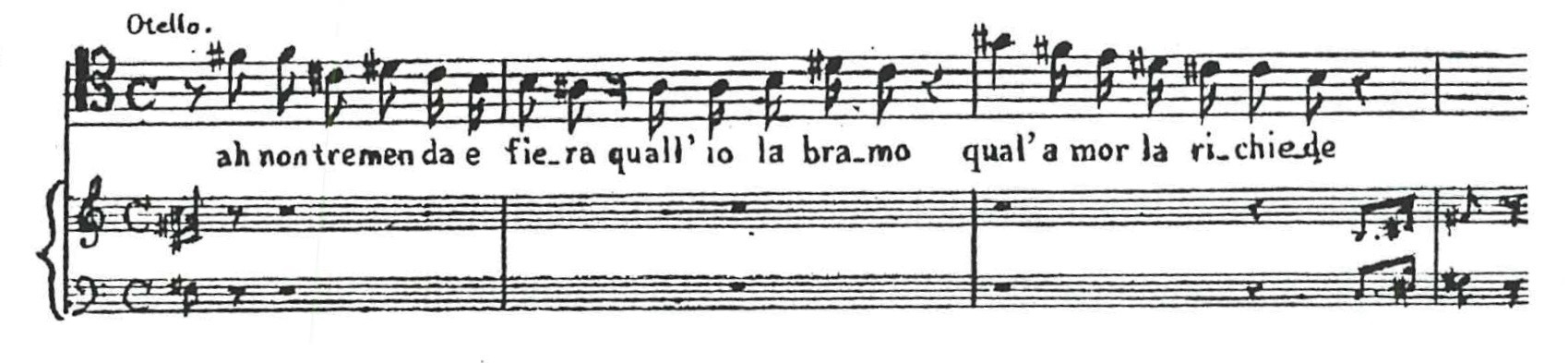

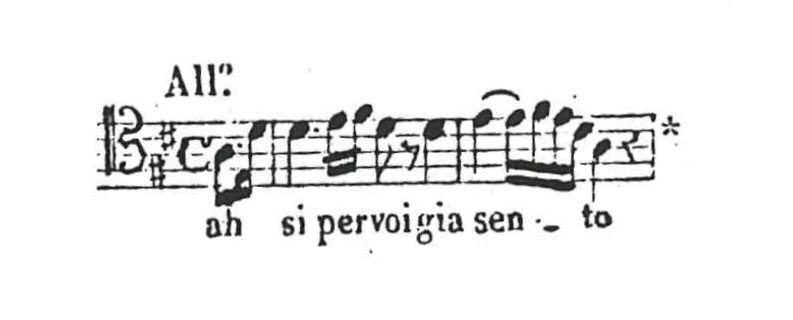

Les notes de poitrine au-dessus du fa, sont insupportables lorsqu’on les emploie en timbre clair dans les chants modérés; mais ici, en raison même de leur effet criard, elles s’approprient aux accents du désespoir et de la rage. On pourrait en dire autant du passage:

Chest notes above F [F1] are unbearable when they are used in a bright timbre in moderate songs; but here, precisely because of their shrill effect, they are suited to the accents of despair and rage. One could say as much of the passage:

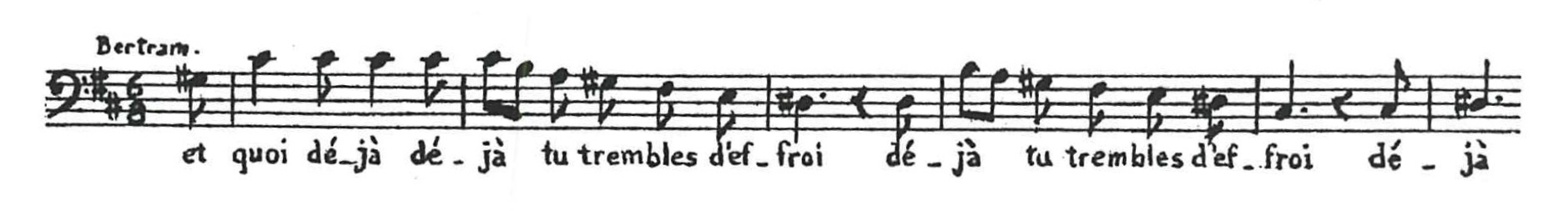

Anger

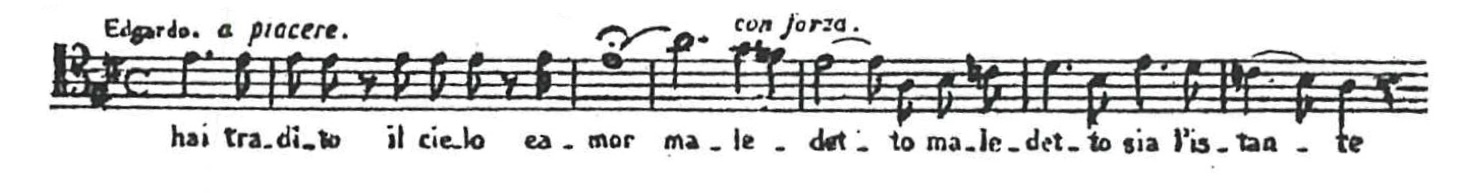

L’indignation, l’imprécation, la menace, le le commandement sévère, arrondissent la voix en la rendant brusque, hautaine. Ex.

Indignation, imprecation, threat, severe command round out the voice by making it abrupt and haughty. Ex.

Indignation

Threat

Cursing

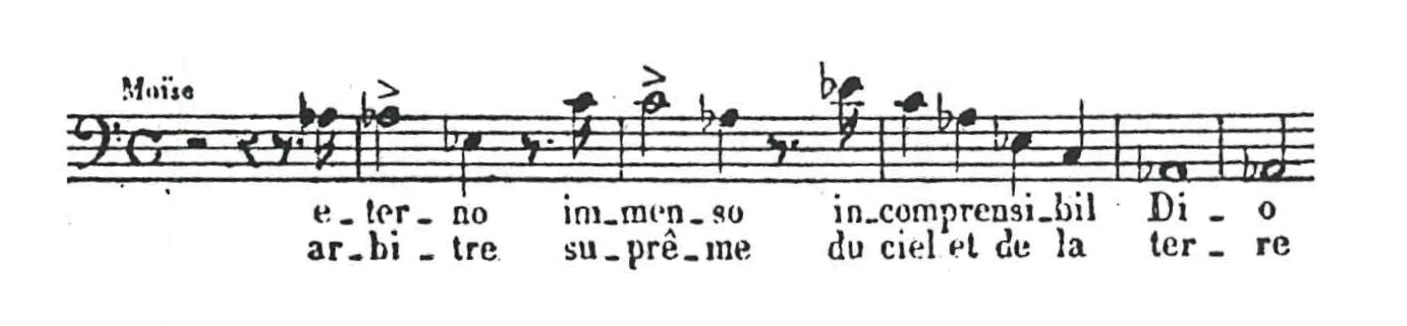

La menace contenue, la douleur profonde et le désespoir concentré prennent un timbre caverneux.

“The contained threat, the deep pain, and the concentrated despair take on a cavernous timbre.”

Threat Stirred up by Profound Hate

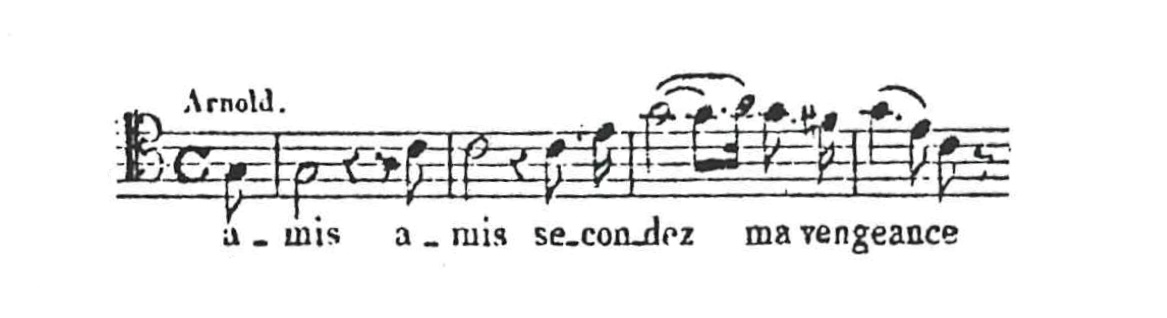

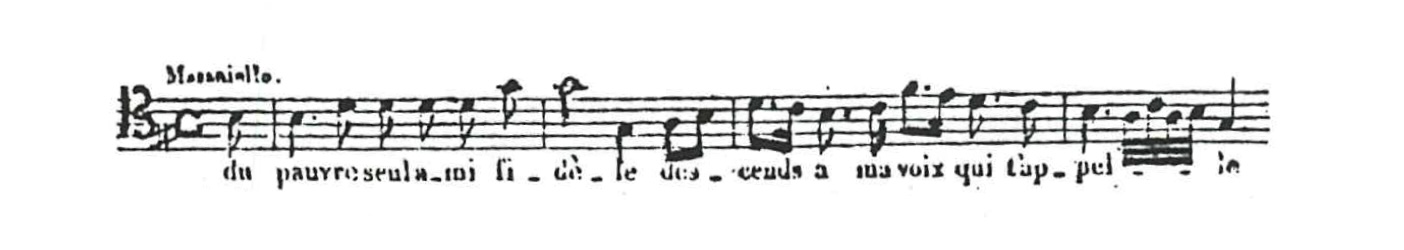

La menace, la douleur, le désespoir qui éclatent, adoptent le timbre ouvert et déchirant. On en voit des exemples remarquables dans les passages qui suivent.

Threat, pain, and despair when they burst forth adopt an open, rending timbre. One sees remarkable examples of this in the passages that follow.

Threat and Bursting Anger

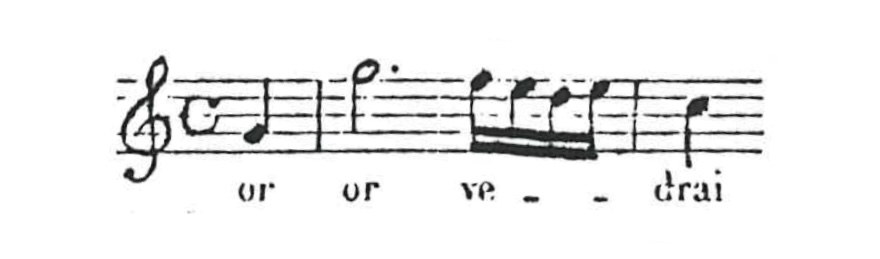

Exaltation

L’exaltation martiale, ou religieuse, arrondit la voix en la rendant claire et éclatante.

Martial or religious exaltation rounds out the voice by making it clear and resounding.

Martial Exaltation

Religious Exaltation

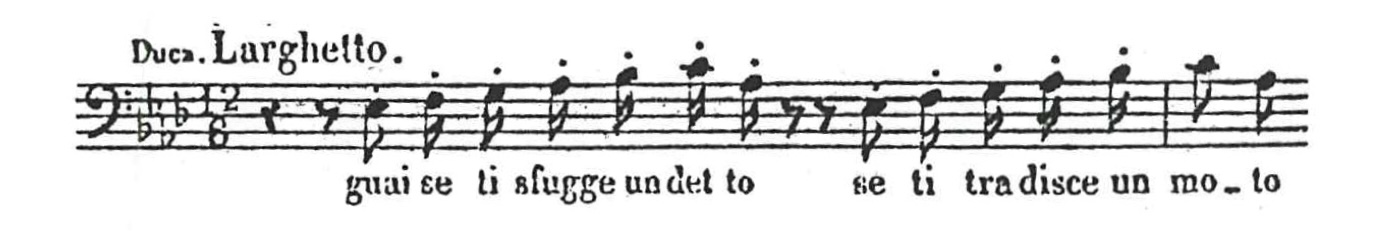

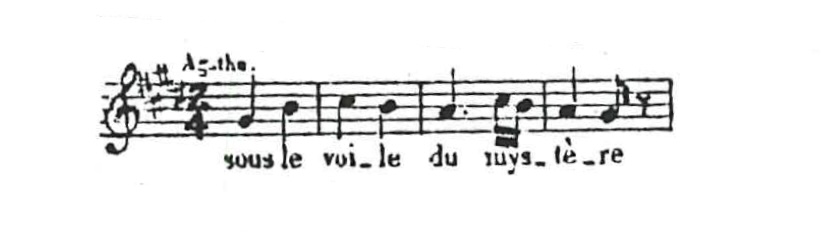

Terror

La terreur et le mystère assourdissent les sons, et les rendent sombres et rauques

“Terror and mystery deafen the sounds and make them dark and hoarse.”

Trouble, Shame, Terror (may need moving)

Le trouble, la honte, la terreur, etc., nuisent à la fermeté des mouvements des organes: la voix devient balbutiante. Les sanglots, la suffocation et l’angoisse achèvent de la rendre irrégulière.

Confusion, shame, terror, etc., impair the firmness of the movements of the organs: the voice becomes stammering. Sobs, suffocation, and anguish complete the process of making it irregular.

Mystery and Threat

Mystery Shaded by Terror and Indignation

Depression

Dans l’abattement qui suit une forte commotion, la voix sort mate, parce que la respiration ne peut être retenue, et vient se mêler aux sons

“In the dejection that follows a strong shock, the voice comes out dull, because the breath cannot be held back and ends up mingling with the sounds.”

Depression

Complaint

Ce caractère mat de la voix est l’opposé du timbre éclatant, métallique, qui convient aux sentiments vigoureux.

“This dull quality of the voice is the opposite of the bright, metallic timbre that suits vigorous feelings.”

Coaxing tone

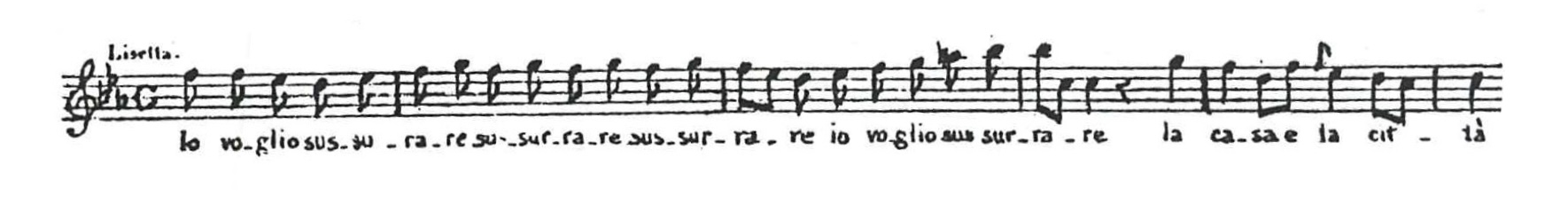

Teasing

La raillerie rend l’organe cuivré, criard

Mockery makes the voice brassy, shrill.

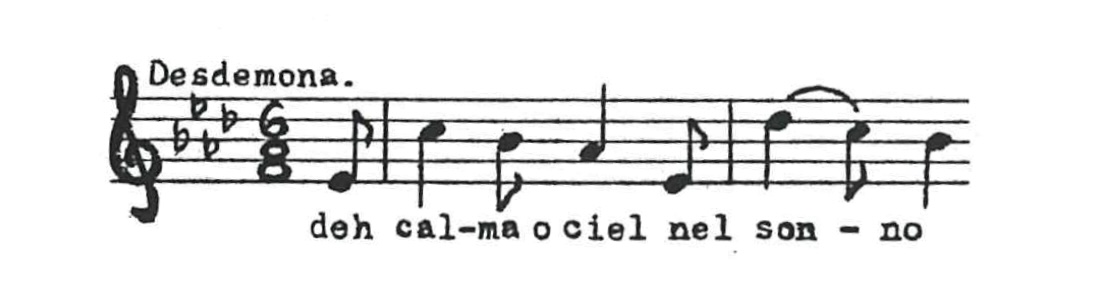

Prayer

Le chois du timbre ne dépendra jamais du sens littéral des mots, mais des mouvements de l’âme qui les dicte. Les sentiments doux et langoureux à la fois, ou bien encore les sentiments énergiques, mais concentrés, ne dépassent point la série des timbres couverts. Par exemple: dans la prière, la timidité, l’attendrissement, la voix doit être touchante et légèrement couverte. Parfois il s’y mêle le bruit de l’haleine dans la tendresse. Exemples:

“The choice of timbre will never depend on the literal meaning of the words, but on the movements of the soul that dictate them. Feelings that are at once gentle and languorous, or again feelings that are energetic but restrained, do not go beyond the range of covered timbres. For example: in prayer, timidity, tenderness, the voice must be touching and slightly covered. Sometimes the sound of the breath is mingled with it in tenderness. Examples:”

Tenderness

Le caractère doux et affectueux que prend l’organe pour exprimer l’amour participe plus du timbre clair que du timbre sombre.

The gentle and affectionate character that the organ adopts to express love owes more to a bright (clear) timbre than to a dark (sombre) timbre.

Tender reproach

Tenderness

Frank Gaiety

Dans la joie, le timbre devient vif, brillant et délié.

In joy, the timbre becomes lively, bright, and agile.

Laughter

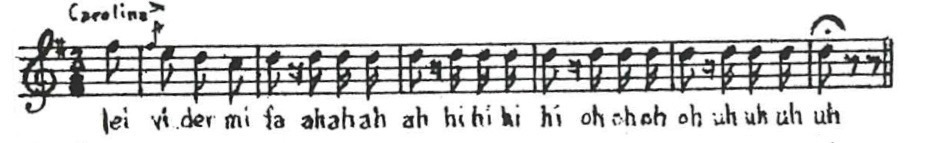

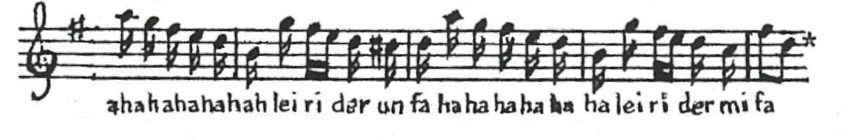

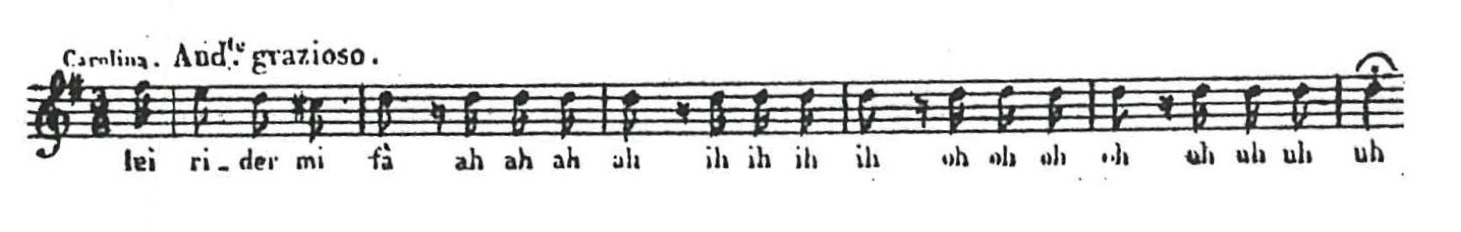

“Le rire est une espèce de spasme convulsif qui ne permet à la voix de s’échapper que par saccades, par secousses. Elle parcourt alors, en montant et en descendant, une gamme peu régulière, mais assez étendue. La respiration demande à être fréquemment et rapidement renouvelée, et ce besoin, joint au resserrement qui s’opère dans l’organe, occasionne à chaque inspiration un râle assez fort. Dans les morceaux on doit éviter le plus possible la roideur et la sécheresse de la note écrite, on doit au contraire imiter l’abandon et la cantilène du rire naturel. Un rire franc et musicalement rythmé ne peut s’obtenir qu’à la suite d’un long exercice.”

Translation: “Laughter is a kind of convulsive spasm that allows the voice to escape only in jerks or shocks. It then travels, rising and falling, over a rather irregular but fairly wide range. Breathing must be renewed frequently and quickly, and this need, combined with the tightening that occurs in the organ, produces a fairly strong rasp with each inhalation. In musical pieces, one should avoid as much as possible the stiffness and dryness of the written note; on the contrary, one should imitate the abandon and lilting quality of natural laughter. A frank and musically rhythmic laugh can only be achieved after long practice.”

Lei rider mi fa

Scene:

Translation:

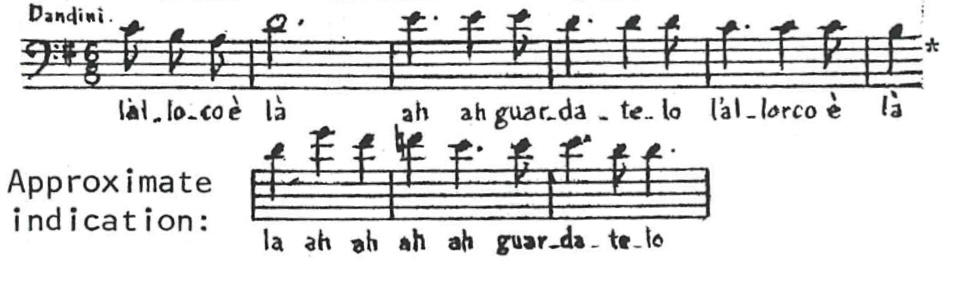

L’alloco e la

Scene:

Translation:

“Le rire appartient exclusivement à l’opéra buffa; l’opéra seria ne peut l’admettre que dans un sentiment pénible déguisé par un rire forcé, ou dans la folie.”

Translation: “Laughter belongs exclusively to opera buffa; opera seria can only admit it in a painful sentiment disguised by forced laughter, or in madness.”

Dans le rire, la voix est aiguë et glapissante, entrecoupée, convulsive.

In laughter, the voice is high-pitched and yelping, broken, convulsive.

Cette première série de timbres forme contraste avec celle que produisent les sentiments gais, ou bien encore les sentiments terribles, mais qui s’abandonnent sans contrainte. Le caractère doux et affectueux que prend l’organe pour exprimer l’amour participe plus du timbre clair que du timbre sombre.

“This first series of timbres contrasts with that produced by cheerful feelings, or even by terrible feelings that nevertheless give themselves up without restraint. The gentle and affectionate character that the organ takes on to express love partakes more of the clear timbre than of the dark timbre.”